How to select the best cover crop species for your farm

© Gary-K-Smith-Alamy

© Gary-K-Smith-Alamy Choosing the wrong species can result in a cover crop that costs you £130/ha or more to establish and still fail to do the job it was grown for.

That’s why the first rule of cover cropping is to consider what you want to get out of the crop well before getting the drill out – especially given the huge array of species and mixes being touted by seed merchants.

Is it to achieve a better soil structure with the ability to direct drill into a quality seed-bed in the spring? Or perhaps bigger yields with the help of nutrient capture and higher organic matter levels?

See also: Part 1: Why farmers should consider cover crops this autumn

Whatever the reason for using cover crops, Niab’s Ron Stobart tells Farmers Weekly that growers must take the time to consider the possible negatives of incorporating them into their rotation and not rush into cover cropping large areas of land.

“Think through how the species will work with the soil type you have, the kit you’ll be using and the crop rotation,” says Mr Stobart.

“One tip I would give to growers is to leave a control area of a field to see if there’s a difference.”

Radish and mustard

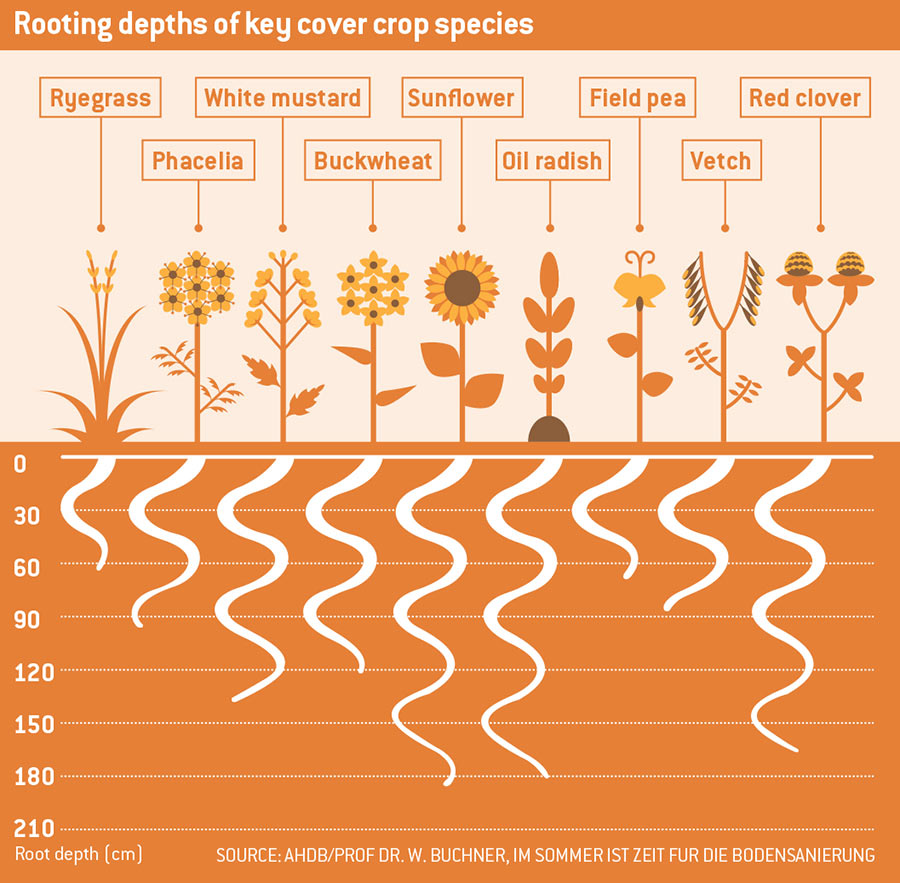

Brassicas such as oil and tillage radish and white mustard are fast growing when drilled in the autumn and can be used to break up compaction, creating channels for crop roots to follow to access water and nutrients.

“There is a bit of difference in rooting type, but generally if you want to get a species with good root growth and a good tap root then a brassica is a good option,” explains Mr Stobart.

The long tap root of the tillage radish is especially effective when used as a compaction buster and can also aid better drainage by leaving open pores travelling deep into the soil profile says Richard Barnes, sales manager at Kings, Frontier’s cover crop division.

“With radish crops you have the opportunity to capture 50-180kg/ha of nitrogen depending on the soil type,” he explains.

“We want to keep that nitrogen in the field and radish is very good because it has a strong tap root, but it also has a fibrous side root network, which means it is great at scavenging nutrients.”

Mr Barnes adds that radish tap roots can pull nutrients that are deep down in the soil profile up towards to the surface, ready for use by the next cash crop.

There are a range of radish species that can help to manage nematode threats in sugar beet and potatoes too.

Phacelia

© Gary-K-Smith-Alamy

Instantly recognisable by virtue of it’s eye-catching pastel blue flowers, phacelia is a popular member of many cover crop mixes.

Unlike radishes, this species is more of a shallow- to medium-depth rooter, helping to give a well-conditioned soil structure.

Mr Stobart points out that a rare quality of this species is that it is less likely to cause problems like bringing in disease that may affect other crops in the rotation.

“One advantage of this species is that it is not related to many other crops that you would typically grow in your rotation,” he says, whereas brassica species for example can harbour clubroot, which could infect a subsequent oilseed rape crop and damage yield potential.

Phacelia is a bulky, branching plant species, adds Mr Barnes, giving good cover of bare ground and encouraging more life to enter the soil.

Vetch and clover

Legume species such as vetch and berseem clover play a big role in fixing nitrogen in the soil after harvest, preventing this from leaching into watercourses and keeping it in the field for the next cash crop as they die back.

While their shallower roots tend to be less beneficial for soil structure, Mr Stobart explains that vetches and clovers should be primarily used for building soil fertility.

“In trials we have seen yield benefits from using legumes and we have had good results with them,” he adds.

Berseem clover and crimson clover both achieve rapid nodulation, which is beneficial because these species will start to hold on to nutrients soon after drilling. However Mr Barnes does offer a word of caution when using these species.

“Remember you should not use a legume cover crop after a crop of peas or beans, use a radish species instead to mop up nutrients.”

Mr Stobart echoes this, adding that legume species are particularly inflexible when it comes to sowing date which can cause issues in years where drilling is delayed by a late harvest or poor autumn conditions.

He recommends that they are to be drilled by mid-August to get enough growth for benefits to be gained from using them.

Oats, rye and other cereals

A key trait of cereal cover crop species like oats and forage rye is vigorous early growth to help give good ground cover overwinter.

These are some of the most shallow rooting of the key cover crop species, but still have an important role to play in soil structure improvement.

“Oats and rye have lots of roots proliferating near the soil surface,” says Mr Stobart. “When grown in lighter soils, they can help hold the soils open and improve soil conditioning.”

This mass of shallow, lateral roots mostly benefit the topsoil, making it more friable and helping in direct drilling or delayed drilling situations.

Forage rye is winter hardy and can be used for grazing livestock in the winter. Mr Barnes recommends pairing this species with a radish species to get a good rooting network running through the soil.

Growers who are looking for a species that will die naturally over winter could consider buckwheat because it’s frost intolerance.

“Buckwheat does give good, quick ground cover and there is some evidence to suggest that it can access pools of nutrients that other cover crops can’t. It’s good at holding on its phosphate for example,” says Mr Stobart.

All you need to know about the main cover crop species

| Brassicas | Legumes | Grasses and cereals | |

| Example species | Mustards, radishes, turnips | Vetch, clovers | Oats, rye, buckwheat |

| Benefits | Brassicas can grow rapidly in the autumn. There is a good understanding of brassica agronomy, which stems from oilseed rape experience, and establishment methods tend to fit in with conventional farm kit. | Legumes fix nitrogen, which can benefit following crops and boost fertility. The amount of nitrogen fixed depends on species, growth and temperature, but is likely to be small with an overwinter cover crop. | Cereals and grasses can deliver good early ground cover which is important where soil erosion is a concern. Other benefits include vigorous rooting. |

| Characteristics | While there are many types and growth habits, autumn-sown brassicas often provide good ground cover and deep rooting. This can mitigate leaching risks, improve soil structure and mitigate compaction. Some species can have trap crop and biofumigant activity too. | In addition to nitrogen fixing, like most cover crops, legume roots can help to improve soil structure; rooting will vary depending on species, field conditions and cover crop duration. | For autumn sowing, these species can establish quickly and some types offer a more flexible sowing date than brassicas or legumes. |

| Drilling date | Often late summer-sown or early autumn-sown at similar timings to oilseed rape. Field conditions and species variety should guide specific sowing dates. | Legumes tend to be slower growing than brassicas and, for autumn use, often need to be sown earlier (late July-August) to aid growth and promote nitrogen fixation. | Drilling times vary with species and can range from July through to September. |

| Considerations | Good autumn establishment is critical to maximise growth, particularly where soil structure or nitrogen capture are key objectives.

Think about potential rotational conflicts, such as clubroot, where vegetable brassicas or oilseed rape are grown in the rotation. |

Consider management around the sowing and establishment of small-seeded legumes, used alone or in mixtures.

There are also potential rotational conflicts, especially where other pulses and legumes are grown in the rotation. |

Management tends to be similar to autumn cereals and grasses.

They may act as a green bridge for cereal pests and diseases. |

Source: AHDB Cereals & Oilseed

Case study: Guy Leonard, RH Leonard Ltd, West Hill Farm, Aldbrough, East Yorkshire

Cover crops made their debut on Guy Leonard’s East Yorkshire farm three seasons ago. Their introduction was driven by his desire to take a more holistic approach to arable farming with a greater range of crops in the rotation and consideration for the vitality of his soils.

Mr Leonard, who farms about 445ha of mainly silty clay loam land some 10 miles north east of Hull, concluded that the soil was holding yields back and turned to cover crops to try and raise organic matter content.

“What we were doing before was not sustainable and we were getting yields similar to those seen back in the mid-1980s in some fields,” explains Mr Leonard.

“Cover crops help us keep the silty clay loam soil that we have here open, stopping it from slumping over winter, improving structure and stopping the decline of organic matter.”

With cover crops gradually being installed throughout the rotation, early test results suggest that they are having a beneficial effect on soil fertility, as organic matter level have risen 0.5% to 3.75% in the three years they’ve been part of a wider soil improvement plan at the farm.

From left: Frontier agronomist Stuart Campbell, grower Guy Leonard and Kings northern technical advisor Clive Wood.

When it comes to species selection, Mr Leonard says he spent a lot of time investigating and researching with Frontier’s norther technical advisor Clive Wood and agronomist Stuart Campbell.

“There were two things that I was mainly looking for: a diverse species mix because that will help the overall soil health and various rooting depths all working well together to help soil structure,” notes Mr Leonard.

He found that appropriate species were dependent on the following crop, Mr Leonard decided to put more cereal species in a mix that came before a broad-leaved crop like spring beans, while more broad-leaved species like tillage radish and peas feature in a mix that comes before a cereal crop.

Berseem clover, tillage radish and phacelia are all good value for money and are good for nutrient capture he says.

“Tillage radish is also great for helping with compacted ground and is a very good way of catching and storing nutrients ready for the next crop.”

However, Mr Wood issues a word of caution, pointing out that in his experience cover crop species can be very regional in term of what works best.

“There are different species but then there are also different varieties within that species, so what can be unique to Guy’s farm might not work as well for farms in another area,” he says.

Planning well ahead is also key, with matters such as available herbicide chemistry, slug control and crop destruction all contributing to a successful cover cropping system.