Growers make the most of fertile soils to achieve bumper yields

Mark Means (left) with neighbour David Hoyles

Some of the most fertile soils in Britain were under the sea 350 years ago, but now see many of the country’s highest wheat yields. Farmers Weekly visits two farmers close to the sea to find out how they are pushing yields higher.

Wheat close to the Wash races away to top yields

David Hoyles looks for a thick wheat crop coming out of the winter. So rather than turning to a flock of sheep to graze it down, he feeds it towards a bumper yield.

Traditionalists might fear that forward crops harbour disease and need these woolly lawnmowers, but Mr Hoyles has the potential to grow 20t/ha crop on his deep, rich, silty soils.

In his south-eastern corner of Lincolnshire, reclaimed from the sea in the seventeenth century, the fertile silts go down at least 18m, giving his crops a firm foundation for record-breaking yields.

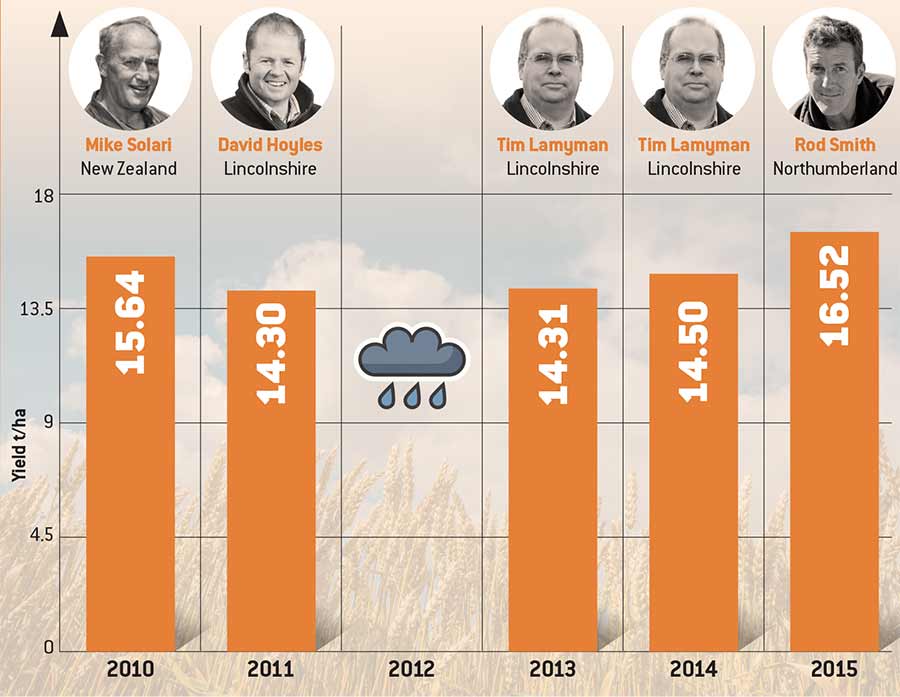

He broke the UK wheat yield record in 2011 with a crop of 14.3t/ha and last season topped that with 15.61t/ha, using similar inputs to those hitting average national yields of about 8.5t/ha.

“We have the potential for high yields, and we are using similar fungicide and nitrogen levels to the average grower and getting nearly twice the yield,” he tells Farmers Weekly.

Key factors for high yield

- Very deep fertile soils

- Wide rotation, including veg

- Good drainage in low-lying area

- Dedicated workforce

See also: Northumberland grower breaks world wheat yield record

Mr Hoyles puts his success down to four factors – fertile and moisture-retentive soils, a rotation heavy with vegetable crops, efficient drains and, finally, a skilled and committed workforce.

Vegetable rotation

Wheat is grown in a one-in-seven-year rotation on his home farm at Monmouth House, Lutton, near Long Sutton, some 3 miles from the sea. He also grows mustard, potatoes, vining peas, sugar beet, beetroot and cauliflowers.

He grows 160ha of winter wheat within his 650ha of arable land – largely biscuit-making variety Britannia and feed wheat Evolution, with the latter variety producing his top yield last year.

This field of Evolution followed mustard, was cultivated with a plough and subsoil combination, power harrowed and drilled in the last week of September at a relatively light seed rate of 120kg/ha with no autumn fertiliser.

Mr Hoyles aims for a crop that will tiller vigouressly to produce 900 tillers/sq m in the spring, which he hopes will give him a maximum of 700 wheat heads by harvest.

With no autumn fertiliser, he applies potash and phosphite in the spring to match his fast-growing wheat crop’s needs.

He is now applying potash in the spring at the T1 timing and in farm trials an application of 45kg/ha has given a yield response of 2t/ha.

This season he will also try phosphite in the spring at T1, and following leaf tissue testing, will apply minor elements such as magnesium, manganese and boron.

Reduced stress

“The less stress the plants have, the more vigorous they will grow and help fight disease,” Mr Hoyles says.

Nutrition experts say he needs 400kg/ha of nitrogen to produce 15t/ha of wheat, so he is pushing up the application rate, which now range from 200kg/ha to 360kg/ha.

However, his top-yielding 15.6t/ha crop of Evolution only got the minimum 200kg/ha of nitrogen following the mustard crop.

The nitrogen is applied in four splits. As he has struggled to get protein up to the breadmaking standard of 13%, he grows biscuit wheat Britannia, which only needs 11.5% protein, and also feed wheats such as Evolution.

His soil organic matter is a relatively low 1.5-2.0% for inherently fertile land, and even with plenty of vegetable matter and ploughed-in straw, he has had difficult pushing level higher in his alluvial silts. Only by introducing grassland could organic matter be boosted significantly, Mr Hoyles believes.

Sea frets

One downside of the farm’s position is that as it lies 2m below sea level, lingering sea frets can encourage disease and block sunlight, while the area’s intensive vegetable growing attracts aphids.

Mr Hoyles’ big disease worry is septoria. He is also concerned about fusarium, but even though he is in a yellow rust hotspot, it is a disease he can manage.

His four-spray fungicide programme includes an azole-chlorothalonil at T0 and T1, with SDHIs only used in high-risk situations. This is followed by a SDHI/azole at T2 and an azole mix at T3 Total spending is about £120/ha.

If no SDHI is used at T1, he is considering using one at T3 to keep late septoria out of his crops.

“It is all about keeping green tissue for as long as possible so that biomass turns into crop yields,” he says.

His wheat variable costs of seed, sprays and fertiliser amount to £455/ha, below the John Nix Pocket Book industry average of £488/ha.

Jack Hill, commercial technical manager at agrochemicals group Bayer ,which runs its own trials on the farm, says fungicide timings are key to guard against yellow rust, septoria and fusarium.

“The timing of fungicide sprays is crucial because of the limited number of spray days due to the sea frets on the farm, he says.

Top-yielding wheat crops

Focus on achieving bumper milling wheat yields in west Norfolk

Mark Means farms only 8 miles east of David Hoyles (see left). However, across the border into west Norfolk his soils are heavier, so he grows more wheat and fewer vegetables.

Here, breadmaking wheats are the order of the day, and last summer he harvested a 14.85t/ha crop of Cordiale, after winning the Adas-organised Yield Enhancement Network competition in 2013 with a crop of 13.41t/ha.

Key factors for high yield

- Maintain a healthy soil structure

- Timeliness of all operations

- Feed crops when they need it

- Good staff teamwork

His slightly heavier silty clay loams suit breadmaking wheats, and Mr Means says 80% of his wheat crop hits the protein requirement of 13% for milling.

“We have the opportunity to replace about 1m tonnes of imported milling wheat. Given the premium and the margin, we should be able to do this,” he says.

He grows mostly Cordiale, but also some Gallant and Crusoe on his 700ha of arable land at The Laurel, Terrrington St Clement, with break crops of potatoes, sugar beet, vining peas and onions.

His silty clays are fragile and easy to damage, so he is careful not to drill too early, as the soil can destabilise and become a “soup” on the top. This can cause root lodging where rooting is not firm enough.

Cultivation is based on non-inversion tillage and his top-yielding crop was drilling on 1 October at a low seed rate of 120kg/ha to produce about 1,200 tillers/sq m, which will likely end up at 600-650 ears at harvest

Mr Means does not want plant populations much higher than that, as the wheat would lodge, so nitrogen tend to go on the crop later to feed it through the season.

Four-way split

A four-way nitrogen split totals 300kg/ha. The first is liquid and the three later ones solid ammonium nitrate.

“We don’t want straw – we want grain. We look to feed the plant when it needs it,” he says.

Mr Means’ fungicide strategy is very similar to that of Mr Hoyles, but he adds one-fifth T1-1/2 spray of an azole + chlorothalonil to protect the emerging leaf two.

Sea frets can limit summer temperatures to help give a longer grain-filling period, but on the other hand they can restrict sunlight and cause fusarium disease problems.

Again, like Mr Hoyles, he is looking at spring phosphate and potash. Therefore he applies the spring phosphate in February/March to help with rooting, and the potash in late March to early April, as it is seen as key ahead of the flag-leaf stage.