Early success for blight-resistant GM potato trial

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener A genetically modified potato variety designed to resist the devastating plant disease blight has successfully come through the first year of trials, say scientists.

Late blight is a global problem that can wipe out whole fields of potato plants if multiple treatments of fungicides are not applied to ensure a good harvest. Worldwide, crop losses because of blight are estimated to be in excess of £3.5bn.

However, scientists at The Sainsbury Laboratory (TSL) on the Norwich Research Park are trialling a Maris Piper potato that has been modified with blight resistance genes from a wild potato relative.

See also: How spud growers will benefit from blight forecasts

“The first year of the Maris Piper trial has worked brilliantly,” said Jonathan Jones, a professor and project leader at TSL.

“We’ve observed resistance to late blight in all the lines.”

Prof Jones said early results suggested blight-resistant potatoes could be a way to control late blight and remove the need for multiple sprays of agrochemicals.

“We have the technology to solve the problems that affect many people’s livelihoods. Crops diseases reduce yields and require application of agrochemicals, and this field trial shows that a more sustainable agriculture is possible.”

The potato modification involved the addition of three genes that enable late blight detection. After the first year of the field trial, scientists observed a marked improvement in late blight resistance.

Gene ‘silencing’

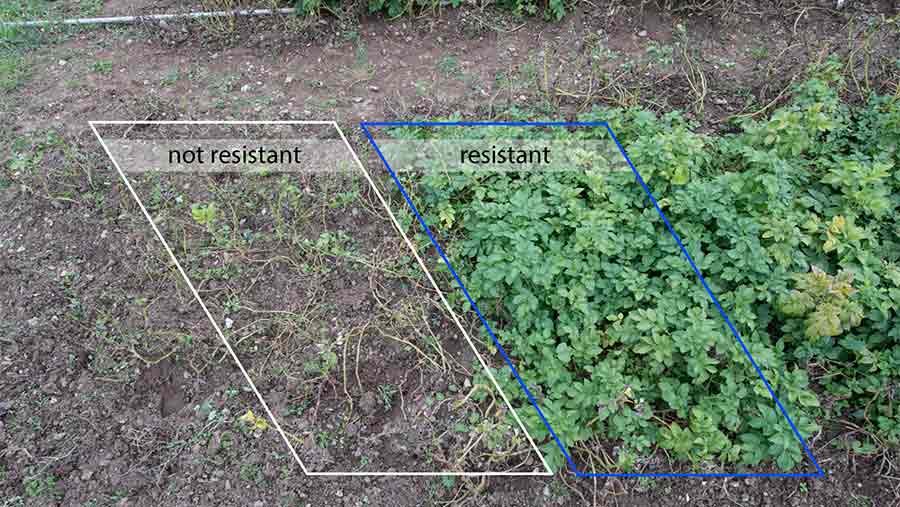

The pictures above show the differences between the resistant plants, which look healthy, and the heavily blight affected non-resistant plants. The plants have been scored for resistance, and the results of the trial will be published following further field trials in future years.

For next year’s field trials, modified Maris Piper potatoes will also carry traits that improve tuber quality. Two genes will be switched off in the plant, a process known as “silencing”.

“This means the new crop will be less prone to bruise damage, making it easier to ensure potatoes meet customer quality specifications,” said Prof Jones.

The work is being carried out with a Horticulture and Potato Initiative (HAPI) grant, funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), and run in partnership with Simplot Plant Sciences in the US and with BioPotatoes in the UK.