Triticale offers benefits over wheat for biofuel

Two separate projects suggest triticale offers additional benefits over wheat for biofuel production. Louise Impey reports

The potential for triticale to become a preferred feedstock for bioethanol production has been highlighted by both HGCA-funded research and an Agrovista biofuels project.

Findings from the two projects confirm the ability of triticale to outyield wheat, at similar or lower nitrogen applications, meaning that the crop could offer both financial and environmental benefits to growers, agree the researchers involved.

Richard Weightman of ADAS, who led the 14-month HGCA-funded work, points out that the higher nitrogen use efficiency of triticale is the key to its possible future in the biofuels market.

“Nitrogen fertiliser accounts for around 70% of the greenhouse gas emissions in cereal production,” he explains. “Triticale’s lower fertiliser requirement means that it offers an opportunity to make greenhouse gas savings, which are important to the processor.”

However, the newer triticale varieties on the market also mean that yields are now comparable to other cereals, he continues. “In our work, triticale outyielded wheat in five out of six trials. At the sixth site, it matched wheat.

“In addition, it appears to produce more straw than wheat. When you bring these three attributes together, any grain price discount isn’t an issue.”

Fertiliser use is an increasingly important consideration with crops for bioethanol, he adds, as carbon reporting for the Renewable Energy Directive now applies at the farm level.

“Previous work has shown that the ideal variety for bioethanol is high yielding, with a low protein content and a low nitrogen fertiliser requirement. Wheat varieties with a lesser demand for nitrogen aren’t currently available, which is why there’s such interest in triticale.”

Laboratory work shows that grain protein contents and predicted alcohol yields are similar for wheat and triticale, he confirms. “Triticale does tend to have a lower specific weight, but it’s not yet known if this is an issue for bioethanol production.”

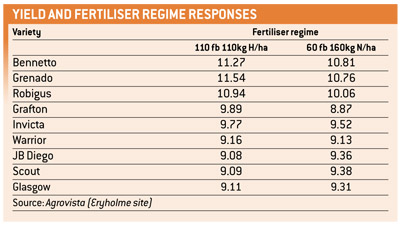

Chris Martin of Agrovista, who carried out a yield and fertiliser regime response trial at the company’s Eryholme site, as part of a three-year biofuels project, reveals that the highest yielding varieties were both triticale.

“This work was investigating variety and nitrogen strategy choice,” he explains. “Nitrogen strategy is important for crops being grown for bioethanol, as its use increases grain protein content as well as yield, which in turn reduces alcohol yield.”

As previous work has shown that earlier nitrogen timings can be used to increase alcohol yields, without affecting grain yield, the trial compared two split application regimes, with one of the regimes splitting the total 220kg/ha nitrogen equally between the two timings while the other stuck to the more traditional approach of applying one-third in the first application.

“We saw that there was no grain yield penalty from applying a greater amount of the nitrogen early,” he reports. “But we also saw considerable variation in grain yield between varieties, with the two triticale types, Bennetto and Grenado, coming out on top.”

He believes that further investigation into triticale is warranted and highlights its potential for second and continuous wheat situations.

Hard wheats

Significant differences were found in the alcohol yields of hard wheat varieties in the HGCA-funded work on cereals for bioethanol production.

The 10 winter wheat varieties, which were grown on six RL sites in 2009, were assessed for their alcohol yield and residue viscosity.

Conqueror and Oakley were found to have the highest alcohol yields, while Ketchum was particularly low. None of them, however, performed better than Glasgow, which was the soft wheat reference in the trial.

“The higher alcohol yield of Conqueror and Oakley is most likely to be due to their lower grain protein contents, which reflect a yield dilution effect, rather than genetic differences,” says Dr Weightman.

There were no differences in the residue viscosities of all 10 varieties, with none having a high residue viscosity, he adds. “That means they’re all the same when it comes to processing.”

Mr Martin agrees that the hard feed wheats can produce alcohol yields close to those of the softer wheats.

“We’ve seen the same results with varieties such as JB Diego,” he notes. “Again, it’s of particular interest to second and continuous wheat situations, as the hard wheats tend to produce higher yields.”

As expected, Glasgow also did well in the Agrovista work. “It’s becoming outclassed now in terms of yield and agronomics, but its high alcohol yield could be a useful trait in breeding new varieties for this purpose.”