Would river dredging help prevent flooding on farms?

© MAG/Philip Clarke

© MAG/Philip Clarke The recent storms Babet and Ciaran unleashed widespread flooding on agricultural land across the UK, costing farmers millions of pounds in crop losses and damage to infrastructure.

Climate scientists warn spells of heavy rainfall are becoming more common due to man-made climate change. Hotter, drier summers and milder, wetter winters are the new norm.

The debate around whether regular maintenance of rivers should be reintroduced has resurfaced following further major floods this autumn.

See also: Video: Farmer jailed for River Lugg damage defends his actions

Beef farmer James Winslade lost 327ha of land to floodwaters during the 2014 Somerset floods at his Bridgwater farm, forcing him to move out and relocate 550 cattle.

In 2015, Defra published a report which concluded that nine out of 10 homes in the area would have been saved from flooding if regular river maintenance had been carried out. Mr Winslade describes this as “an admission of guilt”.

He accuses the government of short-sightedness in its river maintenance policy. For example, the Environment Agency (EA) may have saved about £20m by not dredging local rivers in the 20 years before the Somerset floods.

But the disaster cost the taxpayer a staggering £147.5m.

“If they [the EA] don’t clean the rivers out when it floods, you get tens of thousands of acres under water. This impacts hugely on habitats and a whole raft of animals and insects die,” Mr Winslade says.

“So, wouldn’t it be better to dredge the rivers in a small area versus tens of thousands of acres that get flooded?”

Mr Winslade accepts that no two rivers are the same and some require more maintenance than others. But many are man-made and need regular maintenance.

“Our local river, the River Tone, was redesigned in the 1960s. They [the EA] had not done any work on it for years before the 2014 floods,” he says.

“It’s common sense really. If you’ve got weed and rubbish in a watercourse, it’s going to hold water back.”

Red tape

Mr Winslade says the EA regularly reminds farmers as riparian landowners of their responsibility to maintain the watercourses. But often when farmers offer to do the work, the situation becomes “mired in red tape”.

He accepts the EA has had its annual budget cut by Defra by 50% over the past decade, but says the government needs to be “more proactive and less reactive” in its approach to flood management.

“Farmers have a can-do attitude and want to get on and do the work and can see what’s needed to be done, whereas the EA’s hands are tied by red tape and gold plating everything they do, which means they can’t do what’s necessary.”

Mr Winslade says the government must think outside of the box with global warming and different weather patterns and allowing planners to build homes on flood plains.

“We have got too much water in the winter and not enough storage in the summer. We need to build more reservoirs if the weather patterns are going to stay as they are.”

Lincs flood woes

Lincolnshire farmer Henry Ward suffered serious flooding at his 100ha arable farm in Short Ferry during Storm Babet – the second time it has happened in four years. In total, about 250ha of local farmland was deluged.

Mr Ward says: “We should absolutely be maintaining our rivers and cleaning them out. It definitely works and a case study for this is what they’re doing on the Somerset Levels following the 2014 floods.

“They have not experienced the serious flooding we have had here. Dredging won’t stop flooding 100%, but it will help reduce the risk. More importantly, if your land does flood, the water will drain away more quickly ready for the next downpour.”

‘Rethink strategy’ – NFUS

NFU Scotland president Martin Kennedy used his keynote speech at the union’s autumn conference earlier this month to call for a rethink on dredging rivers.

His plea came after several rivers burst their banks during Storm Babet, flooding swathes of farmland across Scotland, particularly in Angus, and causing millions of pounds of damage to crops and infrastructure.

Perthshire hill farmer Mr Kennedy noted that 30 years ago, river management was seen as a routine and required maintenance. Farmers regularly removed gravel and silt from pinch points along rivers, which helped “enormously” to protect towns and villages from flooding “at no cost to the taxpayer”.

Aberdeenshire farmer Patrick Sleigh says farmers want to get back to dredging rivers like they used to, but they are now heavily regulated by the Water Framework Directive (WFD).

“Government officials appear to protect and value the livelihoods of fresh pearl water mussels and such like, at the expense of human beings,” adds Mr Sleigh, chairman of the NFUS North East environmental and land use committee.

EA response

The EA told Farmers Weekly it was working alongside farmers and landowners to help improve flood resilience in rural areas.

Between 2015 and 2021, flooding and coastal projects were completed that better protect more than 280,000ha of agricultural land, which the agency said helped to avoid £500m of economic damage to agricultural land production.

Furthermore, between April 2021 and April 2023, the EA says it better protected around 148,000ha of agricultural land through the Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management (FCERM) investment programme.

In 2022/23 the EA spent over £200m maintaining flood risk assets. It prioritises this maintenance work to provide the greatest flood risk reduction for people, homes, and businesses.

Ian Hodge, the EA’s chief engineer and director for Asset Management and Engineering, says dredging can be effective and justified and there is no blanket ban on this approach.

“Where dredging and desilting is economically viable, will not harm the environment, and will reduce flood risk, then we will undertake it,” he says.

“We do this looking at other flood risk management measures as part of a catchment-based approach.”

‘No quick win’

But Mr Hodge says dredging is “not a quick win”.

“In most main rivers, dredging and desilting are not the most efficient or sustainable way of reducing flood risk, and may actually increase flood risk to downstream communities and cause environmental damage,” he adds.

“In most places there are much more effective and efficient ways to better protect communities and increase their resilience to flooding.

“For these reasons, the level of dredging and desilting undertaken has decreased in the UK over recent decades.”

Case study: Nick Adames, Bognor, West Sussex

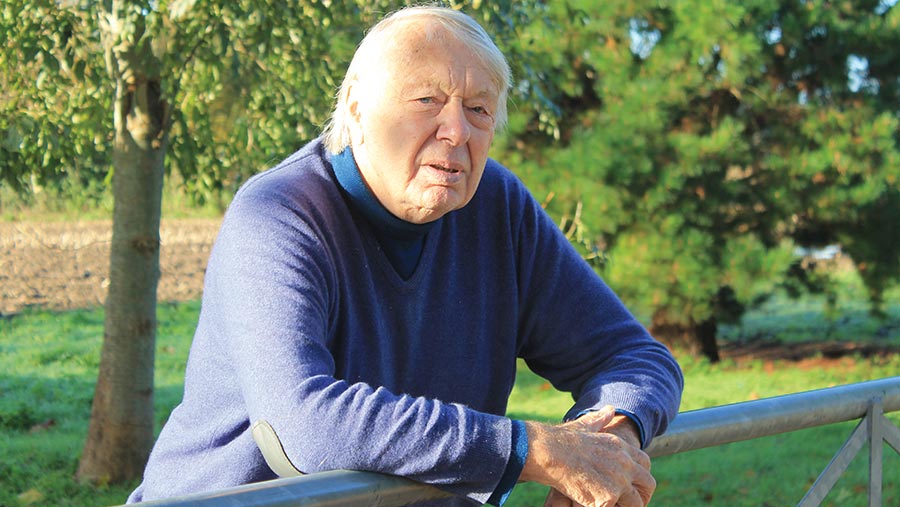

Nick Adames © MAG/Philip Clarke

Nick Adames’ family has farmed on the flood-prone land to the north of Bognor for four generations, so he is all too aware of the problems caused by inadequate drainage and river maintenance.

“Our land is close to one of the many ‘rifes’ in our area – the local name for main ditches dug by hand centuries ago to drain huge areas of wet, low land along the coast,” he says.

“Sea walls were also created in the 1800s, and outfalls that allowed the rifes to drain at low tide.

“More recently, pumps were installed and it all worked well – until the mid-1990s, when the Environment Agency was formed and the previous River Boards and farmer groups disbanded.

“Since then, the whole drainage system has been almost completely neglected. Sea walls were left to collapse, silt allowed to build up, and farmland left to flood.”

This accumulation of silt has also blocked the drains on Mr Adames’ land, stopping inland water levels from dropping to previous levels.

“It’s OK for livestock grazing in dry summers, but worthless for any other cereal crops,” he says.

“Farmers are allowed to clear the small tributary ditches, but most see the work as pointless, when we know the water cannot get away via the rife and outfalls.”

© Nick Adames

Discharge

Compounding all this is the regular discharge of raw sewage into the rife from the local water treatment plant.

“Being silted up, the sewage has little choice but to flow upstream onto huge areas of farmland and coat the ditches, which remain polluted for months and has killed many of our hawthorn trees which lined them,” says Mr Adames.

He also dismisses EA claims that dredging presents a risk to the environment and wildlife. “I have spent many weeks in years gone by clearing waterways, yet the wildlife thrived, creatures were back in the water the next day.

“Now there is hardly any wildlife left in these waterways. Fish, frogs, newts, moorhen, coots, little grebe, once common, are all gone.

“I’m sure there are many farmers across the country suffering the same as us, and all because we have a government agency that is not fit for purpose.”

What are the downside of dredging?

With floods likely to become more frequent, more extreme, and to affect areas that have not witnessed flooding for decades, the plea is often made for dredging.

But just because a practice was once routine, this does not make it the solution for today, argues Ali Morse, water policy manager at The Wildlife Trusts.

“On a local scale it can help to reduce water levels,” she says. “But where heavy rainfall brings flows that vastly exceed the capacity of the river channel, dredging achieves very little.

“Instead, we must find ways to hold more water on the land itself.”

Ms Morse believes compacted soils and field drains channel water down the catchment when they could instead be holding it back.

Ms Morse says farmers must be supported to nurture soils and keep soils/silt out of the water in the first place (negating the need to dredge), and funded to create wetland features – scrapes, leaky dams, attenuation areas – to help manage flood flows, and attract wildlife.

Downsides

And the downsides of dredging only add to this argument, she says.

“Undertaken in isolation, dredging and river re-profiling can increase flood risk downstream, destabilise riverbanks, damage infrastructure and erode adjacent land, all making other flood defences more vulnerable,” says Ms Morse.

“Such measures can create a conduit for agricultural pollution, and cause significant and permanent damage to wildlife and habitats.

“This includes the loss of spawning gravels for salmon and trout, destruction of habitat for juvenile fish, and the removal of features used by protected species like water voles, freshwater pearl mussel and white-clawed crayfish.”

To avoid such harms, any river maintenance must be undertaken with care, with regulatory consent, and as part of a wider programme of integrated water management, she says.

Failure to do so can result in severe legal and financial penalties.